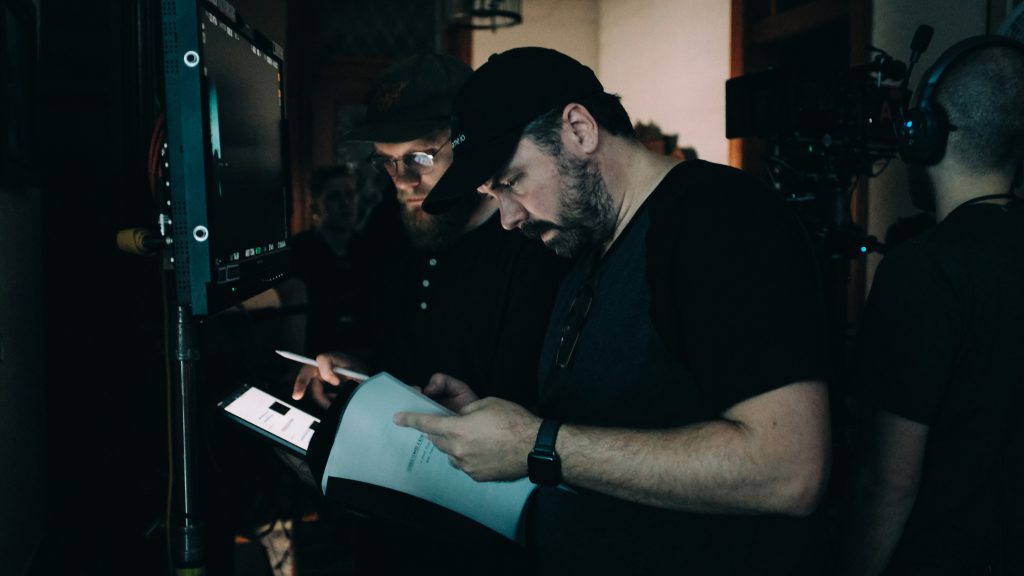

Ryan Connolly’s new short film ‘There Comes a Knocking’ is a proof-of-concept for a full-length feature film. Ryan and colorist Andy DeVries talked to FilmConvert about his visual concepts for the film and how they were realized in the color grade.

Ryan Connolly and Andy DeVries interview

Give us a bit of detail about yourself background profession, how you got into filmmaking and your current role

Ryan Connolly: My background has always been in film. I took odd jobs trying to make money to get gear; I’ve been doing this as far as I can remember, six or eight years old somewhere in that range.

I went to film school a little bit late, nowadays I probably wouldn’t even go to film school but back then this stuff didn’t really exist that exists today, all the information that’s out there. So I went to film school around 20 years old, 21 years old, I went to more of a tech school because I just wanted to know where the buttons were, I didn’t want anybody to teach me how to tell a story or character or alter what my voice would be, I wanted that to be an organic process that I just learned myself after the fact.

I finally got the idea to start Film Riot to get some information out there that at the time really wasn’t there. You had things out there like Indy Mogul which at the time now they’re there they do everything and it’s fantastic, but at the time it was it was more like prop builds and stuff like that which was really cool but it wasn’t all the other aspects of filmmaking, which is what I wanted to get into.

And of course Video Copilot was out there, but Andrew was just focusing on After Effects at the time, so I saw a niche or rather slot there that that could be filled, and I thought it’d be interesting to fill it, and do it in a way that would kind of watch my progress, watch me learn, like, learn with me sort of a thing.

But what got me into filmmaking, it was just my dad brought home the camera and I was hooked from there on out, and I’ve told this story a bunch of times, but it was Jurassic Park that really made me realize, people make these things. Because there was so much behind the scenes revolving around that film that I was aware of, I just became obsessed with that film, because it was the first time I ever felt unsafe in a safe place, it was just the experience it gave me really completely altered my life from then on.

I want to know who this Spielburg guy was, what’s a director, then it just became a complete total focused obsession after that. Before that I was already making my own short films and stuff, I just I didn’t know people did this for a living and never really clicked, and then Jurassic Park solidified everything into it.

In my current role I own Trinue Films which has Film Riot and Variant, and that was just the development over time of trying to get to the point of making future films, putting one foot in front of the other which led me here.

Tell us about your film, how did it come about

RC: It’s an idea that I’ve had for about six or seven years for a feature, and it’s something that I’ve been developing. Then after I put out Ballistic, a lot of producers and managers, agents, and stuff like that started reaching out, and there were several producers that wanted to figure out what a feature version of Ballistic would look like.

So I navigated that for a little while and then landed on my two managers at Three Arts, Will Rowbotham and Luke Maxwell, who were helping to connect me to writers to help develop this into something. I got a producer on it, but it’s a pretty big film, an original sci-fi film with the first-time director that would be a large budget, so getting something like that made is gonna be an uphill battle.

I showed them what I’ve been working on with ’There Comes a Knocking’, which at that time was something like a 52-page scriptment and some look books, pretty much a pitch, and they really responded to that, so I dove headfirst into developing that.

Finally I figured out the way into it and I developed that for several months, we decided that again since I am a first-time director getting this set up somewhere will be a little bit difficult, so something like a proof-of-concept short film that shows the tone and that I can pull off the genre the way timeline and kind of dipping the toe into my vision of what this film will look like and feel like, we figured that that would be really helpful into getting the feature made, so that’s how this came about.

It was interesting writing it because it was writing a moment; something that could exist outside of the feature but something that doesn’t really give too much of the concept away, doesn’t give any of the story away, you sort of just plant a seed that gets people interested and that’s always an interesting thing to do, because there’s people who watch it and be frustrated that you only planted a seed of something didn’t give them a fulsome thing, and then there’s people that would love it, so that that’s always interesting to put out and watch the reactions for.

Tell us about the visual style of the film. Any specific horror or thriller references you looked at?

RC: I’m a huge David Fincher fan and I think you could definitely see his influence and a lot of my work. Hitchcock for sure and Spielberg for sure, and Spielberg has a great way and so does Fincher in letting scenes breathe, and that’s how I’ve always loved to do horror, and to think of moments putting the audience in the room with that character. That’s the slow move, the slow burn the slow reveal panning instead of cutting, you’re making me feel like you’re actually in that space, feeling that space. That’s usually where I’ll end up.

RC: Quick cutting and the fast move, that that’s for stuff like action when it comes to things like Ballistic, but for something like this I feel like it would be constantly deflating the tension instead of building, and I think the tension comes from silence, from again not cutting, a pan feels like you’re turning your head to look at something where a cut can you pop that or at least deflate a little bit that tension balloon you’re trying to blow up.

RC: So I’m cautious with how much I cut, if it’s more of an action set sequence you start to cut a little bit more to move that pace and get the heart pumping. It’s a balancing act but I think when building tension living in the moment with the character is a lot more important and it was important to me to feel like you were living in the moments with the character as well so slower moves and longer takes is something that I personally am drawn to, when it comes to that sort of idea.

Andy: I pulled reference stills from a number of films with nighttime scenes that I love. Not necessarily horror or thriller (although there was plenty of that), but anything that lived successfully in that lower 1/8 of the luminance scope. Truth be told I am largely a commercial editor and that subject matter tends to be bright and cheery by its nature…so this was a really cool opportunity to push things around in the dark. I looked at what others have done to get a better idea of where the good stuff actually lives on the scopes. I’m often surprised just how low some films can go on the scopes and still held up in the details…its a crazy balancing act for a DP, I’m sure.

How much of the look was captured on set versus created in the grade?

RC: A huge percentage of the look was captured on set. My DP Chase Smith really set out to get as much in-camera as possible. Something we talked about early on, we really landed on the colors that we wanted, and how I really wanted the film to feel in each of the sections. You got the daytime section, and then you got the nighttime section pre horror, and then when we slam into looking at the door at night or in full horror mode so you had those three sections of what I wanted that film to feel like, what I wanted the audience to be feeling, and we talked about that a lot. Had a lot of different image references that we both pooled and landed on for sure what we both knew we wanted this to look like. So he was really able to capture that all in camera and in the grade it was more putting the icing on the cake than anything.

Andy: We stayed very true to the on-set photography. Chase Smith did a fantastic job establishing the look in-camera, particularly the nighttime scenes in the back half of the film. So we spent most of our time in the color grade addressing the contrast and tweaking the nighttime values, keeping the color itself pretty true. We’d step away for a few minutes and drink some coffee, then return with fresh eyes and really try to dial-in how dark was too dark on a given shot, particularly for the pivotal moments of suspense. Despite all the fancy tools at our disposal, it mostly boiled down to good ol’ fashioned dodging and burning (with power windows and highlights in Resolve). The photography was so clean that I could pull some crazy clean keys…but again it was all pretty reigned in. I used a very subtle Look LUT to help shape her skin tones on the opening daytime scene, but otherwise no fancy LUTS aside from the LogC > Rec709 transform.

Tell us about your post workflow from ingest from the camera through to final export and upload

We shot on the Alexa Mini and we had my editor Lucas Harker there who was wrangling all the footage and starting to piece things together so we could do like quick rough assemblies as we shot just to make sure we were getting what we needed. Because this was shot in such a specific way there wasn’t gonna be a lot of room for movement. In the end as much as we baked the look in camera, we kind of baked the edit into the film with how I shot it as well, so everything was very specific. It was nice that Lucas there to be able to assemble things really quickly and see where we were at.

What part did FilmConvert play in your grading?

Andy: We knew we wanted some added grain in post, both for technical and aesthetic reasons. With all the subtle shadowy gradients I knew we’d want some grain to help alleviate any banding or compression artifacts on the YouTubes. And I just love me some grain in general. We looked at some film emulation overlay options as well as Resolve’s built-in grain, but it was feeling distracting. The goal, I think, was to feel the grain…not see it.

Ryan suggested we look at the new Nitrate options and it felt much more organic and effective right off the bat. We were able to adjust the size and intensity depending on the shot. It was also nice to do all the grain work back in Premiere post-color grade…that way we could play with grain without having to re-render out of Resolve at crunch time.

RC: That’s usually the secret sauce every grade I’m involved in, in any kind of way is adding FilmConvert at the tail end of that just to add a little bit of that film grain that just pushes it toward that final filmic look that I personally respond to. It’s that classic cinema feel. I mean obviously the film look is completely subjective, but that icing on the cake that FilmConvert puts on just at the end there it just pushes it that extra ten percent to get it where I really want it to be.